Podcast: Play in new window | Download

During the Industrial Revolution and in the subsequent years before worker protection laws were put into place, it was a matter of course that profits were placed before people. When coupled with the dangerous occupation of mining, one is left with a recipe for disaster.

In Blantyre, Scotland in the wee hours of the morning of 22 October 1877, over 230 men and boys descended into Pits 2 and 3 of the Blantyre Colliery owned by William Dixon. Little did anyone know that by the end of the day the worst mining accident in the history of Scotland would have happened.

The day began at 5:30 am, as it typically did. It was a Monday, and the residents of Blantyre were starting their week. The miners went down to begin their day of harvesting coal to keep houses warm and to power machines.

A known danger in the mines was an extremely flammable gas mixture dominated by methane called Firedamp. It builds up in bituminous coal mines particularly in the areas around the coal being extracted and also in the strata between the layers. As each area is excavated, the gasses are released. Bituminous coal is soft, medium grade coal with a tar-like material pressed in it called bitumen.

In the years leading up to the disaster, miners at Blantyre had voiced their safety concerns, but their words fell on deaf ears. In 1876, several miners had actually gone on strike to protest the hazardous working conditions as well as to ask for a wage increase as compensation for such a work environment. Dixon promptly fired them all.

It doesn’t take much to ignite firedamp; a mere 10% ratio of gas to air is enough. Afterdamp, the carbon monoxide released during the explosion, often follows.

At 8:45 am, a massive explosion rocked the town with the sound heard miles away. Flames shot up from Pits 2 and 3 as the firedamp was ignited by open flames from lanterns taken down into the mine. The alarm sounded but the damage was so extensive it was hard for anyone to get out.

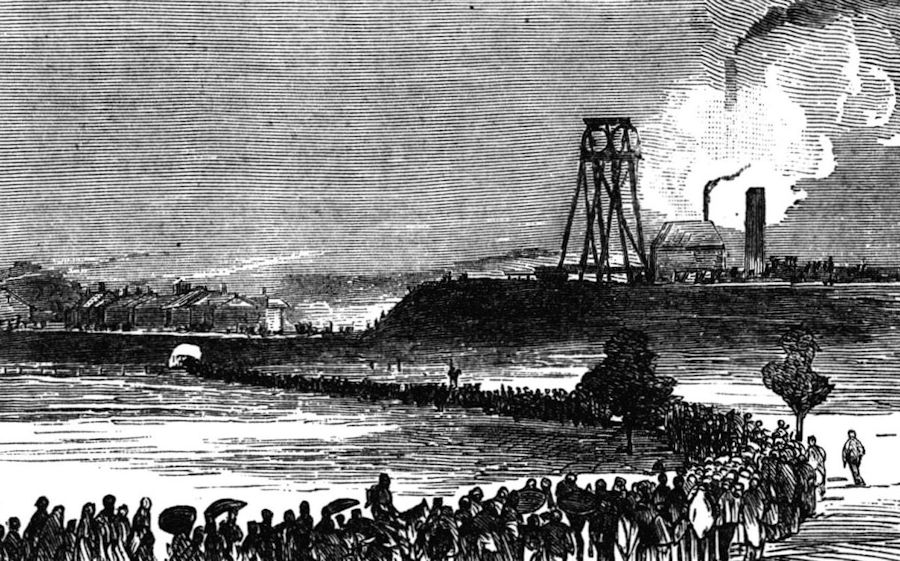

Rescuers worked tirelessly in the rain and autumn chill every day and every night trying to get all of the bodies out over the course of the next three weeks. Crowds would gather at the edge of the mine, so extracting the bodies was tricky as the rescuers tried to keep them from being seen by everyone, especially the women.

Getting the injured miners out of the damaged mine and out to medical facilities was also difficult, and hampered by a lack of supplies and a plan for evacuation. Even those who survived the blast were not safe by any means. Their injuries were so extensive that many died en route to the Glasgow Infirmary.

A temporary mortuary was set up in town and women came to help take care of the dead. They would wash the bodies carefully and place them in coffins with the miner’s personal effects in the bottom of the coffin at his feet. Once everyone was cleaned and laid out, the victims’ families were summoned to identify each one. As each of the bodies was identified, a list of the victims was added to and posted. The mortuary earned its nickname “the Death House.”

Once the miner had been identified, the family was responsible for collecting his remains and preparing for the funeral. Many families were not wealthy, so wheelbarrows were often the standard means of transport. Many of the miners were buried on-site in two trenches, bodies laid side by side.

The living were also cared for in town. Survivors were given first aid and other treatment as necessary, and the rescue party members were fed and given drinks so they could keep going.

The casualties totalled 207 miners who lost their lives, including an 11-year-old boy. Ninety-two women were left widowed, and 250 children had their fathers taken away. In some cases, the women lost all of the males in their families. For other families, there were elderly parents who now had no financial support either. Adding to their grief, a mere six months after the disaster, Dixon evicted 34 widows who had not moved out of the houses which were owned by the mine.

Miraculously, this was the first coal mine explosion in Scotland, but mines in England and Wales had had their share of gas blasts in the past.

Later mine accidents occurred on 5 March 1878 and also on 2 July 1879 at Blantyre, costing another 34 men their lives.

For his part, Dixon put up a large memorial to the two explosions near the graves, but little else was done.

An appeal was sent to the nation for funds to be given to the families that would help relieve the financial burden. “Contributions are earnestly solicited to meet the destitution of the afflicted families,” one appeal read. And contributions did roll in. Rich or poor, people gave to help out, financially and materially including donating dresses and stockings.

An annual march continues to this day to honour the dead and remember the Blantyre disaster.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download